- Home

- Dandi Daley Mackall

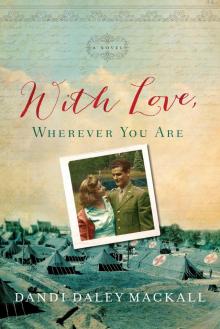

With Love, Wherever You Are Page 4

With Love, Wherever You Are Read online

Page 4

She shook her head at the wino and hoped the sailor could read her smile. Then she started off again, grateful for the added protection of the US Navy.

“Say, doll, how about you and me getting us some bubble juice? I know a real cozy place.”

Helen wheeled around in time to catch the sailor’s wink. He was the whistler? He stuck out his arm as if he expected her to take it and throw herself at him.

“What’s the matter with you, sonny?” The old man came to life and was on his feet in a split second. He grasped the sailor’s arm and twisted it behind his back before the boy knew what hit him. The wino must have been stronger than his emaciated body looked because the sailor struggled but couldn’t get away. “I believe you owe this fine nurse an apology.”

“What? I was just—” The sailor flinched and dipped his shoulder in a way that made Helen think the older man knew a bit about pressure points. “Okay, okay!” he wailed. “I’m sorry.”

“Like you mean it, young sailor,” the old man urged. “And don’t forget you’re talking to a lady.”

The boy bowed his head. When he glanced up, Helen saw that he couldn’t have been as old as Eugene. “I’m real sorry, ma’am.”

“I know,” she said. “Thanks. Thanks to both of you.” She felt lousy for thinking the whistle had come from the older man. That would teach her to judge books by their covers. “And good luck . . . to you both.”

It wasn’t until she reached the corner that she realized an amazing thing. She had just been given the apology, the respect she’d been denied at the hospital today. It couldn’t have been a coincidence. Her mother would have said it had come straight from Gott im Himmel. God in Heaven.

Instead of turning up Sherman Avenue, she walked the extra blocks to Lake Shore Drive. Helen could hear waves crashing seconds before the blue waters of Lake Michigan came into view. An icy wind made her shiver, and she buttoned her jacket, then stuck her hands back into her pockets. Choppy whitecaps smoothed out toward the horizon . . . and beyond.

She slowed as she passed the stone mansions with their wrought-iron gates. Ray knew the owner of the biggest house, the one with three turrets. He promised he’d get them invited to a party there. What would it be like to live in a mansion like that? Ray said she’d know soon enough if she’d say yes to one of his marriage proposals.

Footsteps sounded behind her. “Helen! Hold up!” Her roommate, Lucille Green, trotted up beside her. “What happened? You never leave early. McCafferty was breathing fire. Did you two have a run-in?”

“Did we have a run-in?” Helen repeated. “More like a run out.”

“How’s that again?”

“I quit.”

“You dope. You did not.” Lucille laughed, but her smile faded when Helen didn’t join the laughter. “Eberhart, say it isn’t so!”

Helen shrugged and started walking again. “It’s so.”

“Wait!” Lucille ran after her. “You’re telling me you actually quit? And you meant it?”

“I meant it all right. Say, maybe they’ll make you head nurse! You deserve it.” Lucille was such a good gal. When Helen had been picked head nurse over gals with years’ more experience, Lucille hadn’t let anybody say a word against her. And Lucille cared like crazy about patients, even the spoiled ones.

They walked in silence up Nurses’ Row to their dorm. Then Lucille used her long stride to get ahead of Helen and peer back into her face. “I can’t believe you really and truly quit. Holy cannoli. So what are you going to do now?”

Helen stopped short in front of the door to their dorm. She could see her reflection in the window, dark-blonde hair in a windblown pageboy, blue eyes stunned wide open. What was she going to do? Was it possible the thought hadn’t occurred to her until now?

“Helen? You okay, Eberhart?” Lucille slipped past her and jerked open the door. “It’s freezing out here, in case you hadn’t noticed.”

Dazed, Helen followed her friend inside, where they were hit with a blast of hot air. She’d been flying high, filled with the euphoria of leaving those spoiled women behind. But what lay ahead? Where would she work? Where could she live? She’d have to leave the dorm. You couldn’t stay there unless you were a student nurse or you worked as a registered nurse for the hospital, like she did. Like she used to do. She’d never find a room this cheap.

“I’ll bet you haven’t even talked to Ray about this, have you?” Lucille said, shrugging out of her wool jacket.

“Ray? Why would I? He’s a great dancing partner; that’s all.” Helen knew her friends thought she and Ray were an item. Ray did too. But she’d never pretended to want anything but dancing from the guy. And she’d turned down every proposal the second he made it.

Lucille elbowed her. “Incoming at ten o’clock. Make a run for it?”

Mae Rogers, the old Red Cross woman who haunted the dorm, was heading straight for them. That tireless vulture in her starched blue uniform trolled the lobby day and night, waiting to pounce on nurses with a fresh load of war guilt.

Rogers touched the tip of her cap, which never budged from the precise apex of her wiry, gray-black hair. She had a bird face, right down to the pointy beak and BB eyes that were trained on Helen. “Evening, ladies. I suppose you’ve heard the rumors about the upcoming all-out invasion on the Jerries.”

“We try not to listen to rumors, even war rumors,” Lucille quipped. “Helen and I keep our radio tuned to Guy Lombardo and Glenn Miller and Kay Kyser. We don’t allow the Trib in our dorm room. Too darned depressing. Just the same, we hear enough war gossip to bring us down, thank you very much.”

“Helen?” The Red Cross woman leaned in so close Helen could smell her chicken-noodle breath. “Have you thought about your brothers today? How many are in harm’s way tonight? Four? Five? What if they’re wounded in battle, bleeding and moaning on the muddy field far away on foreign soil? And what if there is no nurse who can tend their wounds? One might find the fortitude to crawl to a nearby hospital, only to find it empty.”

The spiel wasn’t much different from the barrage of words fired on nurses night after night as they tried to get to their rooms. But Helen could picture the scene.

“Come on, Helen,” Lucille urged.

Usually, at this point in the harangue, Helen ducked out, dodging the “Red Cross–fire” as if her words were bullets.

Not this time. She stayed where she was.

“Helen,” the volunteer persisted, “have you given thought to your brothers’ plight over there?”

There wasn’t a day that went by that Helen hadn’t thought of her brothers and wondered where they were and what they were going through. She’d prayed for them. She’d tried to believe that was enough. “Yes, I’ve thought about my brothers. Golly, yes.”

Poor Mae Rogers looked shocked, as if her bullet words had ricocheted and struck her head-on. She’d probably expected the usual jokes at her expense, or a strong defense against her melodrama. Her bird face drew taut, dubious. “Well . . . yes. Of course you have. That’s good.”

Helen wasn’t kidding herself. She wasn’t being swept up in some false sense of guilt that she was putting her brothers in danger by staying in America. In fact, Wilbur, for one, would have tied her to the bedpost to keep her from going if he hadn’t been off fighting in Europe. Clarence and Bud would laugh themselves off the decks of their ships at the thought of their sister in the Army. Ed, already an MP in England, would lock her up and swallow the key. And Eugene would call her Gypsy and accuse her of wanting to roam the world like her ancestors.

Helen glanced around the lobby at the war posters she walked by every day: the one with the sad, strange man in a wheelchair; the one with the young nurse receiving her white cap under the slogan Become a Nurse, Your Country Needs You. Another poster had a woman in an Army uniform smiling, the light making her look angelic: Enlist in a Proud Profession: Join the US Cadet Nurse Corps. A dozen gals had told Helen she was the spitting image of the poster girl.

/>

Helen knew that Nurse Benchley and others had joined up in a wave of patriotic fervor after Pearl Harbor. If she hadn’t been in nurse’s training, she might have been swept up along with them. But she couldn’t quit training. And when she got out, there was a position at the hospital, an opportunity that might never come around again. The war, on the other hand, felt like it would go on for the rest of her life.

Now she didn’t have that job. She didn’t even have a place to live. She sure as heck wasn’t going back to Cissna Park. She still wanted to be rich, but she also wanted to do big, important things with her life. To see the world.

A group of nurses rushed in, chattering and giggling, and the Red Cross volunteer, apparently sensing fresh prey, started off toward them.

“Wait!” Helen cried.

Mae Rogers frowned back at Helen, no doubt expecting a wisecrack. It wouldn’t have been the first. “What is it this time?”

“Where do I sign up? I’m going over there.”

ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI

MARCH 1944

Frank stood in the hospital payroll line and tried not to imagine what the Army would do to him when he showed up late for basic training. He’d written letters and made phone calls, trying to get them to understand that there was no way he could get to El Paso, Texas, the day after graduating in St. Louis, Missouri. Nobody listened.

He and Anderson and almost every other resident he knew had enlisted with deferments so they could finish their residencies. Deferment had been a good deal, ensuring they’d enter the Army as lieutenants. Griffin and Diaz, who had interned with him in Miami, hadn’t enlisted, and they’d been drafted as privates, pulled out of residency, and sent overseas. Nobody knew where they were now.

Frank was not his old man. Dr. Pete Daley, as much soldier as doctor, had been the first Missouri physician to sign on to help train medics. Frank, on the other hand, still couldn’t believe he’d let himself be dragged into this mess. He’d been counting on the war being over by now.

“So, Dr. Daley, how does it feel to finally get those MD initials on your name tag?” Nurse Margaret Stemmons scooted in front of him and fingered the letters: F. R. Daley, MD. Maggie was the biggest dish on the nursing staff, voted so by secret ballots from the male medical staff. Nobody wore the whites like Nurse Stemmons. With her long blonde hair, she could have doubled for Veronica Lake, and she knew it. “Ready to conquer the world, Doctor?”

“I don’t know, Maggie. Do you think I’m ready?”

“Don’t tell me Frank Daley, MD, is finally doubting himself . . . just a bit?” She put a hand on his arm, showing off bright-red nail polish. “Is there a unit you haven’t worked in at this hospital? Let’s see . . . burn unit, disease ward, cardiac, ob-gyn, ER, orthopedic—”

Frank interrupted. “That one was punishment imposed by the chief after that little prank backfired in the ER.”

He joined in Maggie’s banter, but his heart wasn’t in it. His medical training readied him for a top-notch, high-paying hospital, not some medical tent on the other side of nowhere, which was where the Army would send him if he survived Camp Barkeley and six weeks of drills, marches, and obstacle courses. Frank’s buddy Lartz had already reported there for duty, and his letters made Frank consider going AWOL before he was even present without leave.

“Are you sure you can’t celebrate with the nurses tonight?” Maggie asked.

“Tempting.” He grinned down at her. He was already going to be late for training. What could it hurt to show up later than late? What would the Army do? Shoot him twice? Probably.

Maggie turned to Anderson, next in line behind Frank. “How about you, Dr. Anderson?”

“Delighted to oblige the nurses, as always.” Anderson knew how to work the system. Somehow he’d gotten himself forty-eight hours before he had to report. The guy had a Clark Gable confidence most people couldn’t resist.

The line moved up, making Frank next in line after Bell, who had to report for basic in North Carolina.

Frank glanced at his watch, the one his folks had given him for graduation. His dad had worked hard his whole life, delivering babies in exchange for lettuce and tomatoes or meat from the butcher, bread from the baker. The watch must have chipped into their savings. Frank wasn’t sure what Dotty and Jack had received for their graduations, aside from lavish parental praise for being valedictorians. To Frank, the not-valedictorian, the watch was a reminder of what must have been approval from the old man, even though he hadn’t said so.

It was almost five. Even if the bus got in on time, he’d never make it to Texas by roll call the next day. Buses were crammed with soldiers, and they stopped at every town.

Maggie interrupted his thoughts. “Say, that’s you, big boy.” She pointed to the hall speaker.

“Dr. Daley. Paging Dr. Frank R. Daley.”

Frank’s body stiffened like it did every time they paged him, which had only been five or six times in two years. He always expected bad news. His dad’s heart. Dotty.

“Dr. Daley, report to the nurses’ station by administration immediately.”

He was already at administration. Frank reached in front of Bell, grabbed his own paycheck, and moved toward the nurses’ station up the hall.

“Dr. Daley, come to the hospital phone at the nurses’ station! General Maxwell is calling Dr. Frank Daley.”

“Hey, Frank!” Anderson called after him. “What’s going on?”

“Beats me!”

He was out of breath when he reached the nurses’ station. Fine soldier he was going to make. Anderson, Bell, Maggie, and half a dozen others were right behind him. Frank turned to them. “This is a mistake, right?”

Anderson shrugged. “You better take it anyway.”

“Is one of you Dr. Daley?” The nurse behind the counter held the phone away from her, as if she were afraid of the thing.

“I’m Frank . . . Dr. Daley, but I think there’s been a mistake.”

“Huh-uh.” She swallowed so hard it looked like she had an Adam’s apple. “It’s General Maxwell, and he wants to speak to you.” She lowered her voice and added, “He doesn’t like being kept waiting.”

“What’s a general want with him?” Anderson asked.

“Are you sure he wants Daley?” Frank couldn’t think of a single reason why a United States general would want to talk to him. “Not Bailey? Or Paley?”

The frightened nurse shook her head and stuck the phone in Frank’s face.

Maggie moved in closer. “Wasn’t there a general in here with a ruptured appendix last April? Didn’t you assist on that?”

“Must have done a crack job,” Bell said, slapping him on the back. “Well done.”

“I guess.” Frank had assisted in loads of surgeries with lots of doctors. And generals looked the same as civilians on an operating table.

“There was a general on the malaria ward last year,” Anderson said. “Or was he a colonel? Maybe he’s a general by now.”

Dr. Reed, the senior staff on duty, dropped a chart on the desk and leaned in. “Take the call, Doctor.”

“Right.” Frank took the phone and instinctively turned his back on the little crowd. “Frank Daley here. Dr. Daley.”

“Finally! It’s about time.” The voice was gruff, muffled . . . but there was something familiar about it.

“Uh . . . I’m sorry I kept you waiting. Is there something wrong? Or something I can do for you, General?”

The crowd around him had grown to a dozen, their whispers hissing like steam from a leaky radiator. Frank frowned at them. “Shhhh!”

“You tellin’ me to shush?” demanded the voice on the other end.

“No, sir. General.”

“All right then!” The gruff voice transformed. “Because you should never shush your big brother.”

“Jack?”

“Jack?” Anderson’s brow wrinkled and he tried to get closer to the phone.

“General Maxwell’s first name is John, I think,”

one of the residents whispered. “John . . . Jack. Probably a nickname.”

Frank remembered his audience. “Sorry, General. Tell me what you need.”

“This is so exciting,” Maggie whispered.

Frank moved away as far as he could, keeping his back to them so they couldn’t see him smile. It was just like his brother to impersonate a general. In college when Frank’s freshman English prof was a no-show on the first day of class, Jack, a junior business major, had shown up out of nowhere and pretended he was the professor. He’d taught the class for a week before the real prof showed up.

“What exactly can I do for you, General?” he asked, risking a glance at his captive audience.

“Get your gear and be out in front of the hospital in fifteen minutes. That’s an order!”

“Will do!”

The phone clicked off, so Frank handed the receiver to the nurse. “Thanks.” He turned to Anderson and the others. “I have to go.”

Frank took off for his locker, shouting good-byes to his baffled buddies. He was outside in time to see a jeep pull into the hospital drive. The horn honked their old code—four longs, two shorts—and the jeep screeched to a halt inches from his feet.

“Hey, little brother!” Jack, in Army dress greens and a military lid, left the motor running and vaulted out of the jeep. He grabbed Frank’s duffel bag and flung it into the back. Then he gave him a bear hug that lifted him off the ground. “Come on!”

Frank threw in his backpack, then climbed in just before Jack hit the gas. “Good to see you, Jack!” he shouted over the roar of the engine. “We were worried.”

Jack flashed him that toothy grin of his. “Told you not to.”

“Listen, you better take me straight to the bus station. I have to be in training camp tomorrow.”

“Why do you think I’m here?” Jack bellowed. “Did you really think I’d let you go to El Paso without me?”

“But how did you know?”

“I have my ways,” Jack said in a terrible German accent.

He had his ways, all right. Further evidence that he was a spy. Jack had signed up in 1939, when the government had appealed to accountants to help organize the armed forces from the inside out. The select group of pencil pushers were called Thirty Day Wonders because that’s how long they committed to service in the US Army. Only the “wonder” had come months later, when thirty days stretched to ninety, then a year. None of them had gotten out of the Army as far as Frank knew. And he was sure they were all part of some secret service, maybe the new OSS. It was no use asking Jack about it. He never said or did anything he didn’t want to, and he always did exactly what he set out to do. Frank thought his brother was a true hero, even though people might never know it.

Just Sayin'

Just Sayin' Eager Star

Eager Star Gift Horse

Gift Horse Cowboy Colt

Cowboy Colt Natalie and the Bestest Friend Race

Natalie and the Bestest Friend Race Buckskin Bandit

Buckskin Bandit With Love, Wherever You Are

With Love, Wherever You Are Runaway

Runaway Horse Gentler in Training

Horse Gentler in Training Crazy in Love

Crazy in Love Dreams of a Dancing Horse

Dreams of a Dancing Horse The Silence of Murder

The Silence of Murder The Secrets of Tree Taylor

The Secrets of Tree Taylor Night Mare

Night Mare Natalie Wants a Puppy

Natalie Wants a Puppy Bold Beauty

Bold Beauty Larger-Than-Life Lara

Larger-Than-Life Lara My Boyfriends' Dogs

My Boyfriends' Dogs Dark Horse

Dark Horse Horse Dreams

Horse Dreams Friendly Foal

Friendly Foal Unhappy Appy

Unhappy Appy Mad Dog

Mad Dog A Horse's Best Friend

A Horse's Best Friend