- Home

- Dandi Daley Mackall

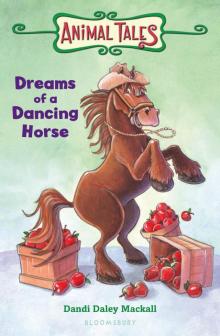

Dreams of a Dancing Horse

Dreams of a Dancing Horse Read online

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

1. Born to Dance

2. Crystalina the Ballerina

3. Work Horse

4. The Big Plan

5. Horsing Around at a Hoedown

6. The Moneymaking Scheme

7. Tractor Tragedy

8. How Now, Brown Cows?

9. Home on the Range?

10. Cattle Drive—Cowpoke Jive

11. Pony Boy

12. A Horse Named Priscilla

13. To Market, to Market

14. A Painter’s Dream

15. If Horses Had Wings …

16. The Big Mambo

17. Good Night and Good-bye

18. All Danced Out and Dreamed Out

19. Circus Plow Horse

20. Queens and Princesses

21. On with the Show!

Imprint

For Cassandra Eve Hendren—dance, Cassie, dance!

1

Born to Dance

You might not believe me, but I was born to dance. Yes, yes, I know. I am the biggest horse you’ve ever seen. Head as large as a sack of grain. Hooves the size of dinner plates.

But never you mind. I, Federico, was created to feel the music of the spheres deep down in my horsey soul.

From the minute I could stand on all four of my wobbly colt legs, I could hear music. It reached into every part of me, from my scraggly forelock to my shaggy fetlocks.

“Hey! Fred! Watch where you’re going up there, you big lug!”

That rude fellow is Round Rollo Quagmire, the driver of this plow and the son of Herbert Quagmire, owner of Quagmire Farms. Rollo looks like a haystack with legs. Coarse yellow hair, beady eyes, and a round body.

“Giddyup, Fred!” Rollo screams, snapping his whip.

Quagmire Farms is a small operation with a one-horse plow. Young Rollo is shouting at me. Humans have always insisted on calling me Fred.

I force myself to put one giant hoof in front of the other. But inside, I am imagining each step as part of a grand dance.

There! Hear the cry of that mourning dove? As always, I can’t stop my neck from swaying and my mane from waving, even in this still and windless Oklahoma heat.

In the next pasture, cows are mooing. The music of it sets my hooves to shuffling in a four-four time: shush, shush, shush, shush.

Dogs bark in the distance, and my legs pick up the cha-cha beat: bark, bark, bark-bark-bark; bark, bark, bark-bark-bark.

“What a clumsy nag!” Rollo yells, snapping his reins on my rump.

Humans.

It’s always been the same story. Why, I’ve been sold as Fred the Plow Horse and passed from farm to farm since the day I was born.

Humans aren’t the only problem either. I’ve never fit in with the other plow horses I’ve worked with. Not that I haven’t tried, mind you.

At Willow Creek Farms, the plow horses accused me of putting on airs. But seriously, was it my fault if I was never at home plowing? Federico was destined to dance, not to plow.

At the Equestrian Center outside Oklahoma City, where I got assigned field-plowing duties, there were gorgeous Lipizzans and Thoroughbreds in the main stable. Plow horses were housed in the old barn. I didn’t complain. And still, most—though not all—of those plow horses teased me for walking and talking like the upper-class horses in the main stable.

I tried to get along with my coworkers. Honestly, I did. “Please don’t get me wrong,” I begged my barn mates after enduring a week of heckling from them. “You’re all wonderfully fine fellows, and I’m ever so proud to work alongside you.”

“Oh, listen to the gentleman, will you?” said Pogo, the lead plow horse. “Fred is ever so proud of us fine fellows.”

“Doesn’t that make you feel warm and fuzzy all over?” joked Pogo’s harness partner, Big Pal.

The horse laughs that followed rocked the old barn.

How I yearned to fit in with my fellow workers! But I simply did not. Inside, I felt more kinship with the fine-boned dancing horses. They moved on the outside exactly the way I felt on the inside. They pranced, their hooves light as air, bounding on the dirt as if on springs. That’s how I, Federico, move whenever I hear music.

When I heard a piano playing from the big house, notes galloping after one another in a mad chase, I could have galloped as fast as the Thoroughbreds. What did it matter that the race horses were sleek and lean, or that I towered over them, bigger than any of the plow horses on the grounds? The music raced through my veins, and I chased after it.

The beautiful Lipizzan performing horses shone white as the fluffiest clouds in the sky. I am painfully aware that my own coat is the dull brown of mud and common dirt. Yet when I heard violins and flutes coming from one of the house windows, my thick haunches became powerful but light. My forelegs transformed into instruments of dance, as graceful as the Lipizzan dancing horses.

But on the dry, red dirt of an Oklahoma field, it was a different story. Fred the Plow Horse was the last horse any creature wanted to be paired with in front of a plow. My knobby legs were hairy tree trunks that stumbled over each other as I walked the rows of dirt, jerking the plow behind me.

And so, after having been bounced from partner to partner at a series of farms and behind an endless number of plows, I have ended up here at Quagmire Farms. It is only my first day at the plow, and already I know that Herbert Quagmire, Rollo’s father, is my hardest owner yet.

“Get moving, you old plug!” Round Rollo shouts. “Pick up your feet, and stop swaying!”

He flicks his leather whip, snapping it against my rump. “What kind of a plow horse are you anyway? You’re the clumsiest creature I’ve ever seen.”

For a second, I can’t help wincing. His words sting more than the whip. Could this young fellow be right? After all, even plow horses think I’m Fred, the clumsiest plow horse they ever worked with. What if …?

No! I blink away the sweat that’s trickled into my eyes. Of course I’m clumsy in the field, harnessed to a plow. Why wouldn’t I be? My moves weren’t designed for plowing. I wasn’t meant to plow fields into neat rows. I was meant to dance.

Turn me loose and set my world to music. Then they’d see. All my clumsiness would disappear.

I shut out the sound of Rollo’s voice and call up the song that is always in my heart. My mother’s song.

Just before my mother died, when I was no more than a foal, she told me, “You will always have my song in your heart, so I will never be far from you. Follow your heart and dance, my Federico.”

Now, under the glaring midday sun, I throw my shoulders into my work and do my best to pull the plow behind me to the beat of my mother’s song.

I am not Fred the Plow Horse. I am Federico the Dancing Horse.

2

Crystalina the Ballerina

I always have trouble sleeping my first night in a strange barn, and tonight is no exception. The Quagmire barn smells like chickens and moldy grain. As far as I can tell, I’m the only horse in here.

I have always attempted to count my blessings instead of my complaints. So now I try not to think about how hungry I am, how small my new stall is, or how lonely it is in here with no other plow horse in sight.

Instead, in my head I make music out of the sound of crickets chirping, the buzz of a pesky horsefly, the swish of my tail swatting said horsefly, and …

Humming?

I’m almost certain that I hear humming. Human humming.

“Hum dee dum de dum hmmm hummm.”

The soft notes make my heart spin. It’s all I can do not to burst into dance right here, right now.

Then I see h

er. The notes are coming from a little human. A girl barely bigger than a newborn filly is humming in the dark. And she’s not just humming. She’s dancing.

The barn is dark, except for a streak of moonlight that floods the path in front of the stalls. The girl twirls and spins, as if she’s floating on the moonbeam.

I hold my breath as the girl spins my way. Her arms sway gracefully above her head, and she twists her way up the aisle, barefoot and dancing on her toes. It’s the most beautiful sight I’ve ever seen. How could I have imagined such a thing would appear in this shabbiest of barns?

For a second, I wonder if she could be an angel … although I would have thought angels dressed better. She’s wearing jeans that have holes in them and might better fit Round Rollo. They’re so big that the poor, thin waif has tied a string of hay twine around her waist to hold up her pants.

Closer and closer she comes. And the closer she gets, the more light shines from her green eyes. With tiny flutter kicks, she dances from side to side until she’s directly in front of me.

The girl stops. She looks startled, as if she’d been thinking there was no one in the world except her and her music. I recognize that look. I know that feeling.

“Well, hey there, big fella!” She smiles at me and comes as close as she can on the other side of my stall gate. “You must be the new horse I heard Uncle Herbert and Cousin Rollo going on about.”

I’m grateful that she said “horse” and not “plow horse.” Humans almost always assume a horse as big as I am must be a plow horse.

I wish I could tell her what a wonderful dancer she is and how much I enjoyed her song. But I have learned over the years that humans can only understand humans. And not even all humans. It is one of life’s great mysteries.

The girl reaches over the stall door and strokes my forehead. “I already know your name. Rollo called you Fred when he reported to his daddy about your first day in the field. I won’t tell you what he said or what other names he called you, but I didn’t believe a word of it. That boy lies like a rug. If his lips are moving, he’s a-lying. Truth is, Cousin Rollo is about as useless as a sore thumb. He and his daddy—my uncle Herbert—are both meaner than a pack of wet panthers.

“Anyway, Fred, my name is Lena, and I’m mighty pleased to know you.”

I nicker and hope Lena knows that a nicker is a horse’s most friendly greeting.

She shakes her head. “I’m just plumb sorry about Cousin Rollo. I reckon he’s no bargain behind your plow, him not having the good sense God gave a goose and all. Even his daddy admits that boy is about as useful as a steering wheel on a mule.”

I like the way she talks. The twang and her quaint expressions, even though I can’t say I entirely understand what she’s saying.

Lena stands on her tiptoes, and I wonder if she’s about to twirl away from me. Instead, she reaches up and scratches me behind the ears. It’s the very place I most love to be scratched.

“Can I tell you a secret?” Lena asks.

I nod.

She grins, wide eyed. “Did you just nod?”

I do it again.

“Are you really saying yes? I mean, did you understand me about telling you a secret?”

This time I nod four times. Sometimes it takes humans a bit of effort to understand.

“Well, if that’s not the bee’s knees! You can hog-tie me and call me Mabel!” she declares.

I admit to a bit of confusion of my own. I was certain she said her name was Lena.

“Well, that’s right fine. That’s what that is.” She squints into my eyes like she can see through my head to my tail.

“So about that secret. My real name is Crystalina.” She gets a faraway look in her sparkling eyes. “Sometimes I pretend I’m Crystalina the Ballerina.”

That’s what her turns and twists were. Ballet. This girl should be a ballerina. If she could understand horse, I’d tell her so right now.

The light goes out from her eyes like a candle’s flame blown to smoke. “But it could never happen. I’m an orphan. Poor as a church mouse. Folks think Uncle Herbert was some kind of saint for taking me in when my ma and pa died. I reckon they’d just have to spend one day watching what goes on around here to know Uncle Herbert is no saint, no how. I do all the cleaning and cooking and most of the chores. That’s why they keep me on.

“It pains me to say it, Fred, him being kinfolk and all. But that man is a no-account, as ornery as a hound dog and tighter than a fiddle string. Besides which, he doesn’t have a bit of horse sense!”

She laughs at that one, and so do I. Even her laughter is musical, the rise of her high notes sweeping up from her bass. I have a hearty horse laugh myself, which seems to amuse her even further, making her tiny body shake with more laughter. That makes me laugh, which sets her off in a fresh bout of laughter, which makes me laugh again … And so it goes. I don’t know when I’ve laughed like this. Maybe never.

When our laughter finally fades, Lena continues. “I think I’ve always had a hankering to dance, Fred. I used to dream about being a ballerina. I don’t dream anymore. But I still like to dance. And this barn at night is the only place I can do it without getting into more hot water than a kettle. So I hope you don’t mind me dropping in on you from time to time.”

She stays in the barn for a while, scratching and petting me. And humming.

When neither of us can keep our eyes open, she yawns and says, “Nighty night, Fred. Sleep tight. Don’t let the bedbugs bite.”

I watch her drag herself back up the aisle. And still, she does a pirouette before waving a final good-bye.

Once Lena is gone, I check for the bedbugs she warned me about, but I don’t find a one. Still, I sleep standing up.

And I think about Lena. She is without a doubt the nicest human I have ever encountered.

By the time morning comes and the sun peeks over the flat horizon beyond the barn, I have come to a conclusion: I must find a way to help Lena dream again. I have to help her become Crystalina the Ballerina.

3

Work Horse

This morning when Rollo comes to harness me to the plow, I make an extra effort to get a thorough look at him. I admit that I had stopped paying much attention to my drivers since most humans look remarkably alike.

But this fellow is an exception. He is round, with greasy hair that looks a great deal like his straw hat. Half-closed, beady snake eyes sink into his pudgy face. The snake appearance is further carried out by his boots, which appear to have come from the skins of a family of rattlesnakes.

It hardly seems possible that this fellow is part of the same species as Lena, much less part of the same family.

“Get a move on, you lazy lug!” Round Rollo shouts. “Hey! Hold still, you ugly nag!” he whines in his next breath.

Talk about mixed messages.

He struggles with my harness, pulling some straps too tight and leaving others to flop.

Once we’re out in the field, things go from bad to worse. It’s impossible to know which way he intends to plow. He pays no attention to the dry field. Instead, he spends his time leaning on the plow while he reads comic books, pausing to take generous swigs from his thermos. The idea that he can read may be the most puzzling development of the entire morning.

The day wears on, and the sun beats down harder and hotter. I’m so thirsty that I imagine waves of pond water spotting the field. I head for them, but they disappear. Rollo stands on the back of the plow, so I have to pull him as well as the farm implement.

Just when I think I cannot go another step without a drink, I hear the sweet voice of Lena. Fearing it too may be a mirage, a product of my imagination, I turn to face the sound.

“Hey!” Rollo shouts, glancing up from his comic book. “Turn back around, you mule-head! Whaddya think you’re doing?”

It is Lena. She hikes up her apron and rag of a skirt, then waves at me. She’s carrying something in her other hand, but I can’t tell what it is.

&nbs

p; I whinny at her and ignore Rollo tugging at the reins and shouting at me.

“Rollo Quagmire, you stop right where you are!” Lena hollers.

Rollo mutters something, but he does stop. “Go back to your barn chores!” Rollo shouts.

“It’s hot as blue blazes out here!” she yells.

“Tell me about it,” Rollo mutters. He takes another long drink from his thermos.

Lena doesn’t slow down until she’s inches from her cousin’s face. “Did you even bother to take Fred in to get a drink of water?”

“Why should I?” he whines. “It already takes too long to plow this field.”

“That’s because you’re slow as molasses at Christmas.” Lena plunks down the bucket she’s carrying. It’s filled with clear, cool water. She jerks the harness reins out of Rollo’s chubby hands so my head can reach the bucket.

I drink and drink. Never has water tasted this fine.

“Poor ol’ Fred. You’d like to drink the well dry, wouldn’t you?” Lena strokes my neck until the bucket is empty.

I lift my head and nudge her a warm thank-you.

“Aw, isn’t that sweet?” Rollo says, in a tone that leaves no doubt that he does not think it sweet at all.

“I have to go back now,” Lena says, ignoring her cousin. “But I’ll be keeping my eye on you.” She glares at Rollo. “Don’t you worry none about that.”

Lena keeps her promise to look out for me. Every day in the field, she brings me water. Still, the days are tough, turning over the red Oklahoma soil and enduring the tug and pull of Rollo’s reins. Often, the only thing that keeps me going is the sound of my mother’s song in my head and in my heart.

Nights, however, are a piece of heaven on earth. Long after the sun goes down, I wait until I hear the gentle tiptoe of Lena’s ballet dance steps entering the barn. How I love watching her twirl and bend, flutter and flow!

One night when she doesn’t appear on schedule, I am so disappointed that I have to call on my mother’s song. Alone in my tiny stall, I imagine music playing, the song in my heart reaching to my hooves.

Just Sayin'

Just Sayin' Eager Star

Eager Star Gift Horse

Gift Horse Cowboy Colt

Cowboy Colt Natalie and the Bestest Friend Race

Natalie and the Bestest Friend Race Buckskin Bandit

Buckskin Bandit With Love, Wherever You Are

With Love, Wherever You Are Runaway

Runaway Horse Gentler in Training

Horse Gentler in Training Crazy in Love

Crazy in Love Dreams of a Dancing Horse

Dreams of a Dancing Horse The Silence of Murder

The Silence of Murder The Secrets of Tree Taylor

The Secrets of Tree Taylor Night Mare

Night Mare Natalie Wants a Puppy

Natalie Wants a Puppy Bold Beauty

Bold Beauty Larger-Than-Life Lara

Larger-Than-Life Lara My Boyfriends' Dogs

My Boyfriends' Dogs Dark Horse

Dark Horse Horse Dreams

Horse Dreams Friendly Foal

Friendly Foal Unhappy Appy

Unhappy Appy Mad Dog

Mad Dog A Horse's Best Friend

A Horse's Best Friend