- Home

- Dandi Daley Mackall

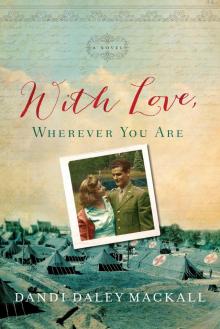

With Love, Wherever You Are Page 10

With Love, Wherever You Are Read online

Page 10

Now, lying in his bunk, the minutes dragged. No danger of falling asleep and missing his chance to call Helen. He wouldn’t sleep until she said yes.

The Army, in its infinite wisdom, had removed telephones from the hospital at Camp Ellis. Doctors were on duty around the clock, so why would anyone need to make a phone call at the Army’s expense? But there was a phone outside headquarters. . . .

After what seemed like hours, snores erupted around the barracks. It sounded like gruel boiling—a bubble here, a bubble there, and finally mad, constant snoring. How had he ever gotten a minute’s sleep in this place?

The last light went out, and seconds later he heard Anderson in the distance, singing: “‘Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer, do. I’m half crazy all for the love of you!’”

The guy wasn’t half crazy. He was 100 percent certifiable. The next line in the song went, “It won’t be a stylish marriage.” Why not just broadcast Frank’s marriage proposal over the loudspeaker?

Anderson stumbled in. He thumped each bed, counting bunks as he moved down the row, immune to the curses and groans.

Great. Now the whole barracks would be awake, and Frank would never get to a phone.

Andy shuffled to Frank’s bunk, where Frank was trying to play possum. “Frank?” he whispered at the level of a normal person’s conversation. “Isn’t marriage a bit drastic, ol’ man?”

“You’re married,” Frank whispered, trying to shield himself from Anderson’s whiskey breath.

“Ah, but not like you’ll be.”

“I’ll take that as a compliment.”

Anderson plopped onto his bunk. “My wife is the happiest woman I know. Alice doesn’t enter into any of my dalliances.”

“Lucky for you she doesn’t,” Lartz muttered.

Andy just laughed, which gave him the hiccups. Thunk, thunk, went the sound of his shoes being kicked off. Two seconds later he was snoring louder than anybody.

Frank knew he shouldn’t go yet, so he conjured up images of Helen. He relived the first time he saw her coming out of the men’s room. Had he fallen in love with her then? Or was it at the Easter service, when she’d hung on every word of the sermon? He could picture each walk they’d taken, the touch of her hand on his arm. She had to feel the same way about him, didn’t she? He couldn’t feel this much unless she did.

Getting her on the phone wouldn’t be easy if she didn’t have night duty. The only number he had was the hospital’s. He rehearsed what he’d say. First, he’d apologize for leaving without saying good-bye. She must know by now that the whole unit had been reassigned. Then he’d let her know how much he missed her. And loved her. And wanted to marry her.

He couldn’t stand it. If he waited one more minute, he’d explode.

Frank pulled on the shoes he’d hidden under his blanket. He’d gone to bed in pants and a T-shirt. As quietly as he could, he climbed down from his bunk.

Lartz got up, his bunk creaking as he did. “Shouldn’t you wait another hour, Frank?” he whispered.

“I can’t.”

“Here.” Lartz pulled the blanket from his bed, rolled it up, and handed it to Frank. “Stuff it under your blanket.”

Frank shoved the roll under his blanket. It looked like a small animal was in his bed. “This isn’t working, Lartz.”

Lartz reached into his duffel bag and came out with his helmet. He had to stand on tiptoes to place it under Frank’s blanket. “What do you think?”

“I think we better hope Sarge drank as much as Anderson tonight.”

“Good luck, Frank.” Lartz held out his hand.

Frank shook it. “Thanks, Lartz. Here goes everything.”

Frank stepped out into a muggy night and flattened himself to the barracks wall to get his bearings. A mosquito landed on his arm and bit before he could swat it. Inside, there had been the stench of too many bodies too close together. Outside wasn’t much better. At one time, the fields around Ellis must have been heavy with the scent of new grain and grass and wildflowers. Now those smells had been replaced with a blend of rancid garbage and pure latrine.

That was it. If somebody stopped him, he’d say he was looking for the latrine. If he got too far away, though, maybe he could claim he was sleepwalking. Anyway, now wasn’t the time to think about getting caught. He didn’t even care if he got caught, so long as he got to talk to Helen first. The thought of her voice on the other end of the line gave him a rush of energy and resolve.

Glancing both ways, he jogged up the row of barracks, keeping to softer ground so his footsteps wouldn’t echo. Crouching as he traversed the open space, he passed the victory garden that, ironically, German prisoners had planted.

When he reached the barbed-wire prisoner section, he spotted two guards in towers, but their backs were to him. He swung south, giving a wide berth to the guardhouse. The farther he got, the better he felt. He had to be close to headquarters, and so far nobody had seen him. He felt invisible. Invincible. He was a man in love, a soldier to be reckoned with.

When he spotted the flagpole, he almost ran for it. The pole stretched up one hundred feet, where the flag flew night and day. A spotlight shone on the red-white-and-blue batting against the night’s breeze. He could clearly see the phone, which was good. But it meant he could be seen once on the phone, which was not so good.

Too bad. Frank made a dash for it as if he were under machine-gun fire. Without looking back, he grabbed the receiver. When the operator came on the line, Frank gave her the number of Percy Jones Hospital.

“One moment, please.”

He waited while the phone rang. Once, twice, three times. His heart beat twelve times per ring.

“Hello? Percy Jones. Nurse Rider speaking.”

Frank racked his brain to remember Nurse Rider.

“Hello?”

“Sorry. Um. This is Dr. Frank Daley. I was in Battle Creek—”

“Dr. Daley? How are you? You just up and disappeared without a word. You’re not overseas, are you?”

He still couldn’t place her. “I can’t really say where I am. You understand.”

“Army business, huh? We sure do miss you and Andy. Things haven’t been the same around here since you boys left.”

“Listen. I’m kind of in a rush.” He glanced over his shoulder and didn’t see anybody, but he felt like a sitting duck. “Is Nurse Eberhart on duty?”

The lilt disappeared from her voice. “Don’t think so. Nah. I’m sure she’s not.” She yawned. “Listen, it’s nice chatting with you, but I better go.”

“No, wait!” He couldn’t let her hang up. “Is Peggy O around?”

“Sure. I’ll get her.” The line went silent.

Frank clutched the phone and prayed that Nurse Rider hadn’t hung up on him. Finally, Peggy’s brash voice came through the line. “How the heck are you, good-lookin’?”

“Peggy, am I glad to hear you!”

“You sound like you’re hiding out. Those Japs got you in prison already?”

“Not exactly. Listen, Peggy. I have a big favor to ask.”

“This wouldn’t have something to do with a gal named Eberhart, would it?”

“How did you—?”

“I’m not blind, sweetheart. But you’re out of luck. Ebby isn’t on duty tonight. Guess you’ll have to call back.”

Frank knew he was asking the moon, but . . . “Peggy, I need you to go get her.”

“You’re joshing me, right?”

“Nope. I have to talk to her.”

“Frank, I’d have to wake every nurse in the barracks to find her.”

“Do what you gotta do. Please! I’m begging you.”

A rush of air came through the phone, followed by Peggy’s hoarse laugh. “Okay, fella. But you owe me for life.”

“Yes! I love you, Peggy!”

“Something tells me I’m not the one you love. Hang on. This could take a while.”

“Thanks a million!” Frank realized he was talking to dead air. P

eggy was gone.

Now all he had to do was wait.

He waited and waited. His fingers ached from gripping the receiver. His mind played tricks on him. He thought he heard something in the distance. A whistle? It was a whistle. Someone was definitely whistling, and it was getting louder. He heard footsteps coming his way.

There was nothing to do but drop the phone and hope nobody noticed the dangling receiver. He dashed between headquarters and the review stand and dropped to his stomach. Still in view, he’d be harder to see than if he stood by the phone.

An armed MP, still whistling, strolled onto the quad. His short legs traversed the grounds, passing only a couple of yards from the phone.

Keep going! Hurry up! Frank wanted to shove the soldier on his way. What if Helen and Peggy were back? He pictured Helen picking up the phone. What if she thought it was a practical joke? She’d hang up. She’d never let him speak to her again.

The second the MP faded out of sight, Frank scrambled to the phone, which still swung like a pendulum. “Hello? Are you there?”

Nobody answered. He strained to hear voices, noises, anything that would tell him he was still connected, that Helen hadn’t come and gone. How long had it been? Long enough for her to have gotten there and left again?

Then he heard, “Peggy, if this is a prank, you’re going to be sorry.”

Helen. He’d know that voice anywhere.

“Pick up the phone, gal,” he heard Peggy say. “And don’t take this out on me. I’m only following orders like a good Army chap.”

Helen laughed. The phone crackled. Then she said, “Hello?”

“Helen!”

“Frank? Is it really you? Peggy said . . . but I didn’t . . . Where did you go? Why didn’t you at least leave me a note?”

“I couldn’t. Listen, I’m not supposed to be talking to you now.”

“But where are you?”

“I can’t tell you.”

“Ooooh, sometimes I hate the Army. They’re so . . . Army!”

“Helen, I miss you.”

“I miss you too.”

He wanted her to say it again. “I mean I really miss you. I can’t stop thinking about you. I didn’t know it would be like this.”

She laughed, that beautiful, lilting laugh he would have risked everything for. “I know what you mean, Frankie.”

Frankie. She’d never called him that before. He liked it. He loved it. He loved her. And he had to tell her so. Fast. “Helen?”

“Still here.”

Footsteps! He heard footsteps. No. Not yet. “Helen, someone’s coming.”

“Is that bad? Are you in danger?”

He heard the whistle now. The MP was coming back. “I can’t talk. But I have to tell you that I love you, Helen. I do. I love you more than anything.”

“I—”

“This war. It’s crazy. But the one thing I’m sure of is I love you. And . . .” He couldn’t stop now. “I want to marry you, Helen Eberhart. Will you marry me?”

A silence draped over the other end of the line. A cold silence.

Behind him, the footsteps of the MP grew deafening, beating in his head against the emptiness of the telephone line.

“Helen?” He was afraid they’d been disconnected. Yet he could hear her breathing. He gripped the phone. They’d have to pry his fingers away if they wanted to arrest him. He didn’t care. All he wanted, all he lived for, was to hear Helen’s voice again.

And then it came. “Are you out of your mind?”

From: Lt. Helen Eberhart, RN

Battle Creek, MI

Dearest Frankie,

That phone call was so very difficult, and I have been having a hard time trying to write you ever since. Your call was so surprising. I hadn’t any idea that you wanted to marry me. I guess, to be trite, “this is all so sudden.”

I know that you will feel hateful toward me now. You are the finest, most decent boy I have ever known. If I wanted to marry at all, I would marry you. I want you to know that. But I don’t know if I’ll ever get married.

Frankie, do you remember on one of our walks together at B.C., when we talked about marriage and war? We agreed that war marriages are dangerous. (We were, of course, talking about others—“relationship casualties of war.”) When I joined the Army, I made up my mind not to marry anyone. I want my marriage—if I have one—to stick always. You and I haven’t known each other long enough to give us that certainty.

My mother and father have been unhappily married for the past 20 years, perhaps longer. I can only swear to the years I’ve observed them. I never have confessed this to anyone before, but it hangs over me. I believe I sensed it all along: my mother’s unhappiness, my father’s tyranny. That kind of marriage, even when it sticks, is no fun, especially when the child watching can do nothing about it.

I am sorry if I’ve made you unhappy. You are too sweet to be hurt by anyone. I don’t know what else to write, but perhaps you can find a way to understand? Please forgive me.

I would give anything to talk to you in person. Can’t we arrange it? Are you so far off? Can you get a leave? I have the whole day off this Sunday and would come wherever you are if you can’t come to Battle Creek. But we would have more time to talk if you can make it here. Say you can, please?

Love,

Helen

BATTLE CREEK, MICHIGAN

Helen walked—alone—to the hospital in the early morning darkness. Only the click, click of her footsteps cut the silence of dawn. By this time, Frank would have received her letter. She hoped, prayed, that he’d understand and find a way to come to Battle Creek. She’d done a little investigating and discovered that most medical units leaving Battle Creek went to a place called Camp Ellis in Illinois. That couldn’t be too far by train, could it?

Maybe Helen’s unit would get sent to Camp Ellis while Frank was still there. That would be wonderful. They’d have more time to get to know each other. Rumor had it that Helen’s unit, the 199th, could be assigned any day now. Captain Walker claimed there would be a whole turnover of nurses by Christmas.

If only Frank could come back for a day, they could talk through everything. She could make him understand that she did feel about him the way he felt about her. He loved her. He’d said it more than once in that crazy phone call. Her. Helen Marie Eberhart. Out of all the nurses who would have given anything to marry the handsome Dr. Daley, he’d asked her.

And she’d told him he was out of his mind.

Why had she said that? He’d risked sneaking to a phone in the middle of the night, and in so many words, she’d told him to commit himself to a mental institution.

What she hadn’t told him, though she knew it was true, was that she loved him. She couldn’t even write it in the letter . . . except to sign her name with love. Coward. She hoped he’d see that closing, how she’d signed “Love, Helen.” But he’d never know what it had cost her to pen that word.

At least she’d made it clear that she wanted to talk. She’d practically begged him to come to Battle Creek on Sunday, when she’d have the day off. So it was up to him now, wasn’t it? He had to come. He just had to.

Helen stopped in front of the post office. She was too early for mail call, but she spotted a light inside. She tried the door, and it opened. Bulletin boards plastered with typed messages covered both walls. A musty smell made her want to prop open the door. She stood at the counter and peered into the back room. “Hello? Is anybody here?”

The old soldier who ran the post office shuffled out, toting a box of letters. The way his back bent, like her dad’s, she suspected he had severe osteoporosis. “I’m closed.” He used his forearm to push his wire-rimmed glasses to the bridge of his nose. Then he squinted at her, and a wave of recognition passed over his face. “Ah, it’s you, the charming nurse from Illinois.”

Helen returned the smile. “Sorry to bother you. I saw the light and thought I’d see if I had anything. I probably don’t.”

“Eb

erhart, right?”

“I can’t believe you remembered. I’m sorry. I don’t think I know your name.”

“Jones. Jonesy, they call me. I think I saw something for you.” He riffled through the box. His fingers made her think of dry branches scraping the cellar window in Cissna Park. “There it is.” He shuffled to the counter.

Helen took the letter. “Thanks so much. I really appreciate it.”

“You have a good day now, hear?”

“Same to you, Jonesy.”

She didn’t look at the letter until she was outside, but she knew it was from Frank. She walked briskly toward what should have been sunrise, waiting until she reached the benches outside the hospital. Settling under the streetlight, hands shaking, she opened the envelope.

6 July 1944

From: Frank R. Daley, MD

Dear Helen,

I have asked you to marry me and you have turned me down. My first impulse was to pound the telephone receiver against the wall, but thankfully, sense prevailed and I ran for cover seconds before two MPs patrolled the ground I’d been standing on.

In the hours since our call, however, I’ve realized that every woman has the right to say no. Rest assured, dear Helen, this will be the last you hear from me.

First, I am wondering why you thought I asked you to marry me . . . aside from the fact that you question the state of my mental health. Possibly you thought I was lonely, lacking in female companionship. I won’t deny that I feel lonely, but not for female companionship. I’ve never had a lack of that.

I’ve been lonely for you. And that in itself led me to consider how I feel, how I felt, about you.

I’m aware that there are those who want to marry quickly in order to get a larger paycheck while overseas. But if you check with your adjutant, you’ll discover that a nurse is not considered a dependent, and my paycheck would not increase.

Just Sayin'

Just Sayin' Eager Star

Eager Star Gift Horse

Gift Horse Cowboy Colt

Cowboy Colt Natalie and the Bestest Friend Race

Natalie and the Bestest Friend Race Buckskin Bandit

Buckskin Bandit With Love, Wherever You Are

With Love, Wherever You Are Runaway

Runaway Horse Gentler in Training

Horse Gentler in Training Crazy in Love

Crazy in Love Dreams of a Dancing Horse

Dreams of a Dancing Horse The Silence of Murder

The Silence of Murder The Secrets of Tree Taylor

The Secrets of Tree Taylor Night Mare

Night Mare Natalie Wants a Puppy

Natalie Wants a Puppy Bold Beauty

Bold Beauty Larger-Than-Life Lara

Larger-Than-Life Lara My Boyfriends' Dogs

My Boyfriends' Dogs Dark Horse

Dark Horse Horse Dreams

Horse Dreams Friendly Foal

Friendly Foal Unhappy Appy

Unhappy Appy Mad Dog

Mad Dog A Horse's Best Friend

A Horse's Best Friend